Significantly, the average time it takes to accomplish one’s nefarious purpose is around 10 minutes, Steube said. Thus, an attacker can obtain the PMKID via a simple packet-capture tool (Steube used the hcxdumptool). We receive all the data we need in the first EAPOL frame from the ,” he wrote. “Since the PMK is the same as in a regular EAPOL four-way handshake, this is an ideal attacking vector. “The PMKID is computed by using HMAC-SHA1 where the key is the PMK and the data part is the concatenation of a fixed string label ‘PMK Name,’ the access point’s MAC address and the station’s MAC address,” Steube explained in a posting late last week on the attack. That means that the router actually provides it as part of its beaconing, so an unauthenticated attacker can access it by merely attempting to connect to the network. It turns out that the PMKID - needed to log into a WPA/WPA2-secured network - is carried in the RSN IE broadcast in EAPOL traffic. It uses a specialized RSN Information Element (RSN IE) to make that connection work. Embedded within that is Robust Secure Network (RSN) protocol, which is designed for establishing secure communication channels over Wi-Fi.

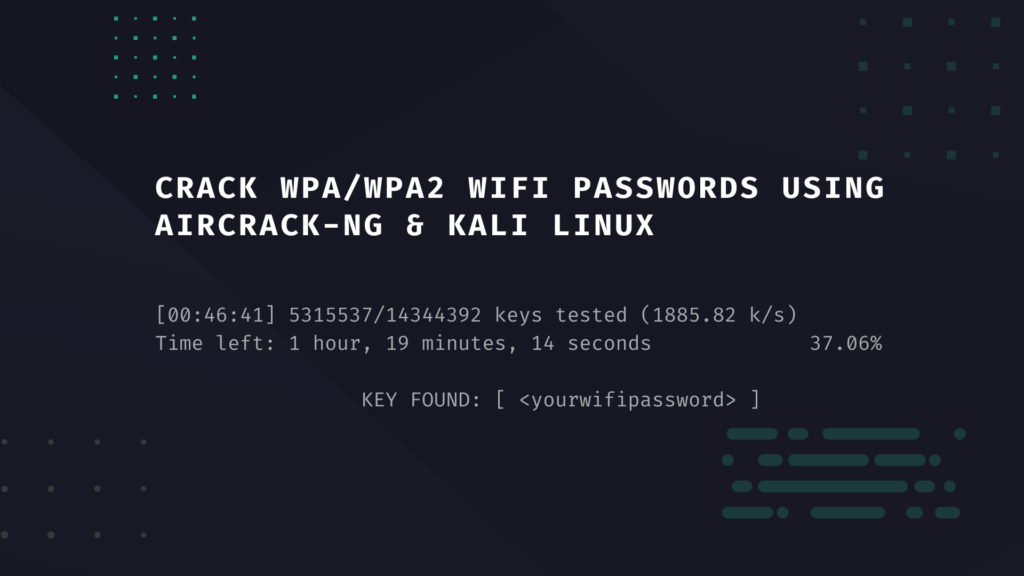

It’s a network port authentication protocol which was developed to give a generic network sign-on to access WiFi network resources. WPA/WPA2 WiFi networks use Extensible Authentication Protocol (EAP) over LAN (EAPoL) to communicate with clients. The new strategy allows an attacker to instead lift the PMKID directly from the router, without waiting for a user to log in and without needing to gain visibility into the four-way handshake. The entire process could take hours, depending on how long the brute-forcing takes, how noisy the WiFi network is and so on.

Armed with this captured piece of information, a bad actor would then brute-force the password, using, say, Hashcat (or another automated cracking tool). That handshake verifies the Pairwise Master Key Identifier (PMKID), which is used by WPA/WPA2-secured routers to establish a connection between a user and an access point. It means waiting for a legitimate user to log into the secure network, and being physically poised to use an over-the-air tool to intercept the information that’s sent from the client to the WiFi router during the four-way handshake process that’s used for authentication. Hackers have compromised the WPA/WPA2 encryption protocols in the past, but it’s an onerous, time-consuming process that requires a man-in-the-middle approach (absent an unpatched vulnerability, that is). He has found a faster, easier way to crack some WPA/WPA2-protected WiFi networks. Legacy WiFi just became a little less safe, according to Jens Steube, the developer of the password-cracking tool known as Hashcat.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)